|

|

THE MOST "FAMOUS MONSTER" OF THEM ALL

A Personal Remembrance of Forrest J. Ackerman

by Steve Vertlieb

| In a child-like land of dreams and dragons dwelt a Pied Piper of imagination, a Santa Claus of fantasy and horror, who lived in the mythical kingdom of Horrorweird, Karloffornia. His name was Forrest J. Ackerman but, to his friends and colleagues, he was simply "Forry."

A generation of wide- eyed children grew up under the spell of his magical influence beginning in 1958, at the tail end of the horror, science fiction and fantasy cycle of motion pictures that had dominated movie screens across the country.

Famous Monsters of Filmland Magazine made its premiere appearance on news stands that year, an enchanted pictorial ticket to a fantasy domain unprecedented at the time. |

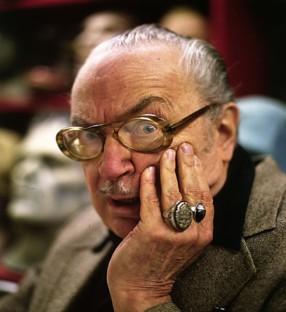

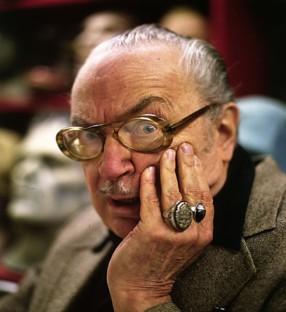

Forrest J. Ackerman |

Famous Monsters, or F.M. as it came to be known, was the first magazine devoted entirely to the horrific legacy of classic horror films, covering five decades of the misunderstood genre with loving attention. For lonely, imaginative children all over the world, Famous Monsters became a wondrous destination. Within its modest pages dinosaurs returned to life, werewolves and vampires stalked the vivid tableau of illustrated nightmares, and gargantuan creatures reached out from beyond their printed domain and pages to excite and exhilarate the senses. Famous Monsters of Filmland became home to millions of boys and girls, a refuge from the mundane, and a tantalizing invitation to unrealized realms of wonder and imagination.

Born November 24th, 1916, Forry reportedly picked up an issue of Amazing Stories Magazine in a drug store located at the corner of Santa Monica Boulevard and Western Avenue in Hollywood at the age of nine, and was instantly hooked. At least, that's the legend.

|

In 1929 he began the "Boy's Science Fiction Club" and, by 1932, had become a founding member and Contributing Editor of The Time Traveler, the original fan publication devoted to science fiction. First Fandom seems to have begun in Clifton's Cafeteria in downtown Los Angeles with the formation, by Ackerman and others, of "The Science Fiction Society," a celebration of the genre by teenage boys who included Ray Harryhausen and Ray Bradbury. |

Their amateur magazine, Imagination, edited by a youthful Ackerman, published the first story by Ray Bradbury in a 1938 issue. During the Second World War, Ackerman edited a military newspaper at Fort MacArthur in San Pedro and, by the end of the war, had opened up his own literary agency. His reputation, honesty, and love for the genre attracted many of the top writers in the field to his representation, including Bradbury, Hugo Gernsback (the avowed "Father" of modern science fiction), Isaac Asimov, A.E. Van Vogt, and L. Ron Hubbard.

The original publication of Famous Monsters of Filmland Magazine ran from 1958 until 1983, under the auspices of publisher James Warren and Warren Publications. As the magazine continued to garner success, it was joined by a happy coterie of brother and sister publications such as Monster World, Screen Thrills Illustrated (devoted to Saturday matinee cliffhangers, and edited by Sam Sherman), and Spacemen (devoted exclusively to science fiction films).

Forry was officially credited with inventing the term "Sci-Fi," claiming that the inspiration came to him while listing to the radio in his car with wife, Wendayne, one afternoon out on the road. The disc jockey on the air referred to a recording as being played in "Hi-Fi." Hence, a youthful generation of fans came to regard their cherished genre as "Sci-Fi."

| I began buying copies of Famous Monsters Of Filmland at the news stand, and at my local pharmacy either with issue six or eight, but quickly ordered the previous back issues as soon as I came to understand what I had lucked into. I was immediately lost in a special treasure trove of joyously terrifying apparitions, and poured over each new issue as an archaeologist might have relished the discovery of an ancient Egyptian mummy. It was somewhere around 1964 when I first encountered Forry Ackerman. |

|

Growing impatient for a more serious or scholarly approach to imagi-movies, and immersed in the cocky deceit of adolescent arrogance, I wrote him a self- righteous letter decrying the juvenile approach of the magazine I had once loved without judgment. To my utter delight, (yet astonishment) came back a lengthy, two-page letter in scholarly defense of my petty diatribe. "Every couple of years or so," he wrote, "someone writes me this same kind of complaining letter about the magazine, and I'll be happy to tell you what I have told them."

He went on in a genuinely kindly manner to explain that he would have preferred to take a more scholarly approach to the subject, but that both his young readers and his publisher had made it clear that they wanted an easier, more accessible approach to the subject of monstrous movies, and that his hands were tied.

I was immediately struck by his gentle honesty and felt guilty that I had been compelled to attack a man and a concept that had given me such immeasurable delight and pleasure over the past four or five years. We began a wonderful correspondence over the next twelve months which I treasured and enjoyed.

|

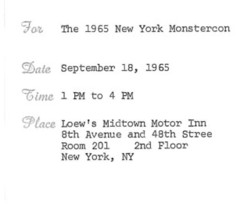

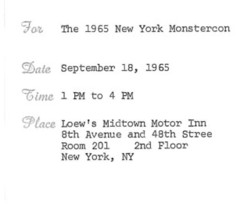

Then, during the early days of September, 1965, I received a tiny envelope post marked from New York. It was addressed to the Vertlieb Brothers and, despite its eastern origin, led me to suspect that it was from Forry. Inside was a note in gold printing that read, simply, "An Invitation from Forry Ackerman." With mounting excitement I opened the folded paper and gasped as I read its contents.

The folded note beckoned my little brother Erwin and I to come to New York City for the first Famous Monsters Convention. It was billed as the 1965 New York Monstercon, and was being held on September 18th of that year from 1 pm until 4 pm at Loew's Midtown Motor Inn at 8th Avenue and 48th Street in Room 201. I was just nineteen years old. My brother was sixteen. We had never ventured outside of Philadelphia by ourselves. My father had taken us to the New York World's Fair the year before, but we had never made this kind of an epic journey by ourselves.

I can still remember the nervous excitement we felt the evening before. I lay awake all night, unable to sleep. As morning approached, we bravely boarded a bus to 30th Street Station and stepped onto the Pennsylvania Railroad car to the biggest city in the world. |

We were strangers in a strange land, innocents abroad, maturing quickly as we walked the busy streets of the sprawling metropolis in search of our monstrous destiny. We arrived at the hotel early, and bravely rode the elevator to the 2nd floor. As we walked through the empty corridor my heart pounded so loudly that I thought it would burst through my chest.

| There...we found it....Room 201. There was no noise emanating from within and, when I reached down my hand and grasped the door handle I found that it was locked. Were we too early, I wondered? Was this the right room? Were we even in the right hotel? We walked back to the elevators and pressed the lobby designation. We were lost and scared, knowing no one in New York. The doors parted when we reached the lobby and there, staring back at us, was the grinning face of an older man I'd come to recognize from the yellowing pages of Famous Monsters. |

|

There he was in the flesh...well, sort of...glasses, moustache, dark hair...wearing a jacket and dark tie.

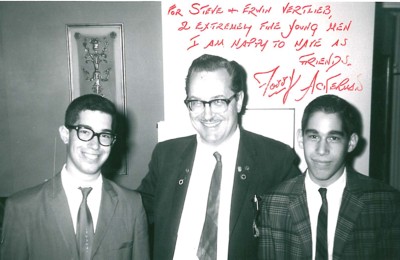

He was 48 years young, and his face bore a faintly mischievous grin. Although I was Jewish, I knew that I had just come face to face with Santa Claus. My brother was busily staring at the elevator floor when the door parted. I nudged him with my elbow, and he looked up. I pointed in a not terribly nonchalant manner at the Draculean figure blocking our path to the lobby. As I did so, the distinguished gentleman before us gave me the "finger," as well, in mock recognition of the importance of this historic moment, pointing to us as I had done to him. "Forry?" I asked. "Yes," he answered with a grin. "Are you the Vertlieb brothers?" "Yes," I answered. I was eloquent even then, you see.

Forry joined us on the elevator as we rode once again to the second floor. By this time, the door had opened to Room 201 and several guests had already arrived. For me and, I suspect, my brother, this was to be a magical afternoon and our introduction to the world of organized fandom. There were many of Forry's adopted children there and it was, I'm sure, the beginning of a wondrous, fanciful voyage for them, as well. There were young fans by the unlikely names of Allan Asherman, George Stover, Gary Svehla, and Walter J. Shank who preferred to be called "Wes."

We all reached out to Forry and to each other, as brothers finding our elusive twins after a lifetime of separation. We were no longer different, or alone. We had found others like ourselves, and it was an invigorating realization. We had found a homeland that none of us ever wanted to leave again.

It was as though the "Book People" in Ray Bradbury's visionary tale of Fahrenheit 451 had discovered others like themselves and had settled into a new reality in which "monsters" were not only okay, but loving and respectable. Frankenstein and Dracula were, in sweet actuality, soft spoken actors bringing culture and artistry to their profession, while The Wolfman and The Mummy brought simplicity to the screen in their portrayal of very normal human insecurity and fear.

We learned that day that being "different" was being special. It was a healthy education, presided over by the gentle writer and film fan seated at the head of the class. We grew to know him as Uncle Forry for he was, indeed, the kindly uncle we had never known; generous, giving, and able to visualize hitherto unknown worlds that sparkled radiantly within our young imaginations.

|

A year or two after that memorable afternoon, perhaps in 1967, Uncle Forry was appearing at a Philadelphia convention as a guest, I believe, of the Philadelphia Science Fiction Society. I asked my mom if I could invite Forry to lunch at our house, and she said yes. I then asked Forry if he'd like to join us for lunch at my house because I wanted to show him my own small, but growing collection of movie and fantasy memorabilia.

He agreed to come, but was concerned about the menu. He had recently suffered a slight heart attack, and was feeling understandably fragile. |

A tuna sandwich on white bread seemed to fill the bill, and he joined us for a couple of unforgettable hours in my personal dream domain.

I couldn't believe it! Forry Ackerman was appearing live and in person at my house. I would have announced it to the neighbors, had they known who he was. I took Forry upstairs to my bedroom where I had proudly displayed my own movie treasures, and he politely acknowledged their importance. I had a small record collection of movie soundtracks, and wanted to play "Name That Tune" with my infamous guest. I pulled out my used recording of the suite From Things to Come by Sir Arthur Bliss on RCA records and he, of course, recognized the familiar themes immediately. The Ackermonster was a guest in my house, and I couldn't have been more proud and happy.

I had always enjoyed writing, and probably began a journal when I was a little boy, writing entire plots for the films I had seen in order to preserve them in my memory. It was the 1950s, and at least one or two hundred years before the advent of home video.

I had attempted more serious excursions in writing by the mid sixties, and had brazenly put together a mercifully short story intended as an unofficial sequel to Bram Stoker's novel Dracula. It was called Dracula Revisited, which wasn't, in retrospect, the most original title for a sequel. Forry liked it, however, and wrote me about a major horror anthology that he was editing for a Spanish publisher in Barcelona. He asked if I'd like to have my short story included in the volume. At his request, I worked very hard at tightening and revising my original story.

Las Mejores Historias De Horror appeared on book shelves in Spain in 1968, and 1969, with a cover credit that read "Recopiladas por Forrest J Ackerman." It was a massive paperback edition that featured a virtual who's who of horror authors and literature, compiled by Forry himself, that included stories by Tennessee Williams, Bram Stoker, Ray Bradbury, A.E. Van Vogt, Theodore Sturgeon, Robert Bloch, John Wyndham, Jack London, Donald Wandrei, Donald Wolheim, Val Lewton and, for fifteen glorious pages beginning on page 79, the newly titled The Second Death Of Dracula by a youthful writer by the name of Stephen Vertlieb.

I was never directly involved in either the creation or production of Famous Monsters of Filmland Magazine, merely its loyal servant. However, during the run of its sister publication, Monster World, I achieved a dubious fifteen minutes of fame in the Fang Mail, or letters to the editor section, in which the assistant editors would often fill the column with fabricated letters from friends. They would change the names, however, in order to protect the innocent. One such name that appeared periodically, you should excuse the expression, was "Steve Liebvert." Ron Borst and Mark Frank had tremendous enjoyment poking fun at their friends and fellow fans in this manner.

In the many ensuing years, I spent considerable time with Forry. We'd meet frequently at conventions held in New York City, and would often talk until dawn about films, actors, music, and our favorite monsters. We'd usually follow up these marathon sessions by going out for breakfast at four or five in the morning at a nearby cafe diner. Forry loved to tell stories about his friendship with Boris Karloff, or about owning the Lugosi Dracula ring and cape.

However, his favorite story was of once having attended a lecture by the immortal H.G. Wells. Wells, he related, was in his latter years and spoke in a high-pitched, rasping voice. Forry mastered his impression of Wells with studious effort, wishing to preserve the legacy of one of our greatest writers by duplicating his voice for future generations to hear. He would grow quiet for a moment, as though emerging from a portal to another dimension, and begin... "I wish to speak to you for about an hour." It was a thrilling moment as Wells spoke to us softly from beyond the grave.

I'd sometimes find invitations from Forry to birthday parties held in his honor, usually in New York. I joined Allan Asherman for one of those memorable evenings in which we were regaled by stories of his youth and love for the genre. Publisher Jim Warren was there, as well, and thanked everyone for coming. I couldn't help feeling special for being asked by Forry to join him at these storied events.

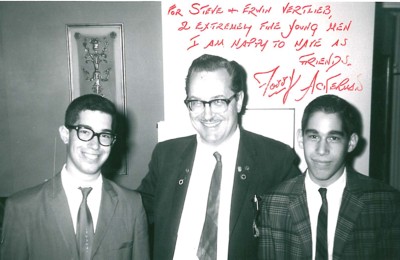

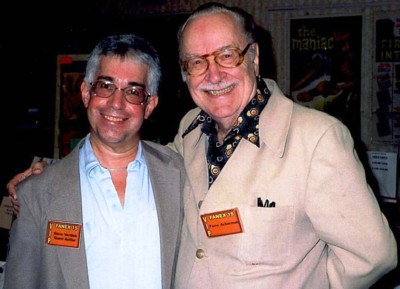

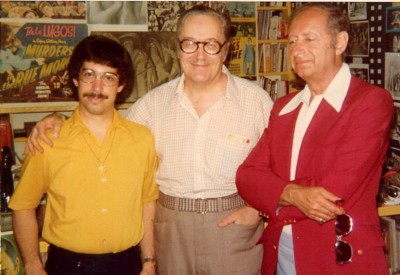

Back: Steve Vertlieb and his brother

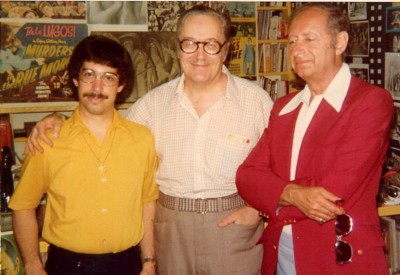

Forry Ackerman and Robert Bloch

|

During my first trip to Los Angeles in 1974, I found myself honored to be in the company of two of my own personal heroes and friends. I had begun a passionate correspondence with Robert Bloch, the celebrated author of Psycho, in 1970. Bob wrote me that if I ever visited the city of angels, he'd volunteer to act as a tour guide, and drive my brother and I all over Hollywood to see the landmark sites. When I arrived, Bob was true to his word.

We drove to Paramount and walked the western streets that John Wayne had once commanded, and visited George Pal's office where the legendary producer/director was working on a teleplay for CBS based upon In The Days Of The Comet by H.G. Wells. Among our stops was a trip to the Ackermansion where Forry Ackerman played host to Bob, Erwin, and I. It was an afternoon I don't think I'll ever forget. |

Forry's mansion was a gargantuan museum of treasured, priceless artifacts from the golden age of cinema and science fiction, and he was a jovial, congenial host, pointing out and highlighting the most famous crowns in his fantasy jewel of a home. The day ended with a dinner invitation from Bob and his lovely wife, Elly, to their home for a wonderful evening of conversation and food.

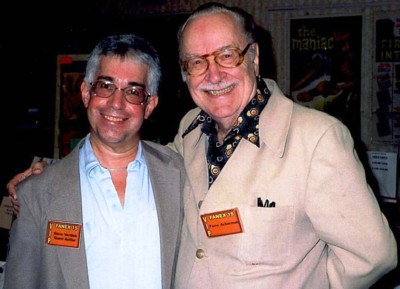

In the early nineties at a Fanex sci-fi convention, either in Baltimore or Virginia, I was asked to host "An Hour with Forrest J. Ackerman." Gary and Sue Svehla had put the convention together with loving hands and, knowing my friendship and history with Forry, asked if I'd consider hosting the hour long presentation. I happily agreed, and spent a delightful hour seated next to the irrepressible story teller.

Knowing Forry's penchant for puns and corresponding punishment, I began the hour by telling the assembled crowd that I had searched high and low for my guest throughout the hotel grounds, but was unable to find him. I walked out into the hotel parking lot, adjoining a nearby park, but "I couldn't find Forry for the trees." Forry stood up, pretending to be offended by the joke, and started for the door. I pulled him back to his chair, promising to control myself in future.

|

Then Forry uttered a terrible, groan worthy pun and, in revenge, I arose in mock outrage and headed for door. He pulled me back to my seat as the audience laughed in understanding approval. When the hour ended, Forry asked me if I'd provide him with a copy of my remarks for his files. I did so happily.

Not long after that, Forry returned to Virginia for The Famous Monsters Convention held, I believe, in 1993. It was an all star conclave featuring hundreds of his best friends. Among the guests was Robert Bloch who, now frail and fragile, mesmerized the crowd with his tales of working on Boris Karloff's Thriller television series. Sadly, I realized that it would probably be the last time that I'd ever get to spend time with Bob. It was. |

During the course of the weekend, there was an affectionate presentation to Forry from each of the countless magazines and fanzines he'd happily inspired. Among these was Cinemacabre, a wonderful magazine I'd played a small part in producing and creating, along with publisher George Stover, and editor John Parnum. John made the speech honoring both Forry and his influence on us "kids." George and I accompanied him to the stage, however, and when the time came for us to leave, I reached down and kissed Forry on his forehead. He smiled, and the audience laughed. It was just my way of saying thank you to a gentle soul who had changed my life.

It wasn't long after that that Forry suffered what may have been a stroke. He never entirely recovered from his illness. He continued to make appearances along with his lifelong friends, Ray Bradbury and Ray Harryhausen, but his health had grown precarious and he appeared skeletal in photographs I'd seen of him. He was forced to give up the Ackermansion, and sell much of his storied collection. He moved into a quiet bungalow, retaining merely a few of his most precious possessions.

In 2007, during the Labor Day Weekend, I read that Forry was attending World Con, the world science fiction convention in Los Angeles. A film that I had appeared in, Kreating Karloff, was being screened at the convention, and I wanted Forry to have an opportunity to see it. I contacted his personal assistant, Joe, and asked him to make sure that Forry was seated in the auditorium when the film was presented. Dutifully, Joe notified Forry of the screening and he sat through the one hour documentary. The following week I sent Forry an E-Mail asking if he had enjoyed the movie. He wrote back that he enjoyed it very much, but that he was perplexed by the appearance of the gray-haired old gentleman in the movie who bore my name. I chuckled, and wrote back that "You should talk."

At Thanksgiving, 2008, we all learned that Forry was, perhaps, ringing down the final curtain of his celebrated life and my prayers, as well as the prayers of thousands of boys and girls around the globe, went out to him.

"Little Stevie Spielberg," George Lucas, and John Landis were among the countless fans, friends, and admirers who reached out to Forry in his final days to thank him for a lifetime of imagination. I telephoned him, but he had retired for the evening, exhausted but gratified at the expression of love and homage filling both his telephone and mailbox. I left a lengthy message on his machine in which I told him of my love and affection for him, and how deeply he had impacted so many generations of creative artists. I spoke with Joe the next day to ask if Forry had heard my message. He told me that Forry had indeed listened, and that he had smiled at the sound of my voice.

Forry seemed to rally for another couple of weeks, confounding his doctors and, for a time, it appeared that he was growing stronger. I thought that he might beat the odds after all. I put it out of my head for a few hours. I was visiting some old friends in Baltimore on Friday, December 5th when I heard the news. As fate would have it, I was sitting in George Stover's living room, seated next to the friend I had first met those endless years ago in New York at the very first Monster Con in 1965, when the text of a heartbreaking E-Mail message appeared on his screen. Forry Ackerman had died. We both sighed. It was a very sad and deeply felt sigh. Uncle Forry was gone. The lives we had so joyously inherited from this sweet, youthful old man would simply never be the same again. He's resting now in the fabled "Metropolis" of his favorite film, traveling above the futurian cities of a fantasy sky line along with Boris Karloff, Lon Chaney Sr., Lon Chaney, Jr., Bela Lugosi, Peter Lorre, and Fritz Lang. The narrator's voice is a familiar one to Forry, as H.G. Wells and company welcome him home at last.

|

Click on the icons for new features in The Thunder Child.

Radiation Theater: 1950s Sci Fi Movies Discussion Boards

The Sand Rock Sentinel: Ripped From the Headlines of 1950s Sci Fi Films

|

|

|

|